Read more about the artists work on: Time heals all wounds? | Part I ->

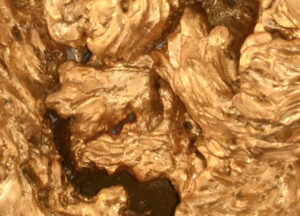

Akanthus, 2018, Messing, Gips, 66x50x30 cm | Acanthus, 2018, brass, plaster, 66 x 50 x 30 cm

Sobald der Name „Akanthus“ im Zusammenhang mit Kunst genannt wird, denken die meisten an eine der drei klassischen griechischen Säulenordnungen (dorisch, ionisch, korinthisch), denn die jüngste – die korinthische – war ab dem Ende des 5. Jahrhunderts vor Christus in Griechenland präsent und charakterisierte sich aufgrund der stilisierten Verwendung der Blätter des stacheligen Akanthus im Kapitell einer Säule als dieser Ordnung zugehörig. Jedoch waren diese griechischen Architekturformen tradierte Überlieferungen und wurden nicht schriftlich festgehalten. Weshalb gerade diese Pflanze gattungsprägend wurde, versuchte zwar der römische Architekturtheoretiker Vitruv (1. Jahrhundert vor Chr.) mit einer Anekdote zu erklären, doch bleibt diese im Bereich der Legendenbildung und kann keineswegs als tatsächlicher Ausgangspunkt gesehen werden.

Die stilisierte Verwendung des Blattes fand in den folgenden Jahrhunderten seinen Einsatz in Wandmalereien, Statuen, Buchmalerei und in der Malerei, jedoch mit mehr oder weniger starker Präsenz. In der Epoche des Barock „erlebte“ die Verwendung des Akanthusblattes einen Höhepunkt, wobei oft auch der Name „Laub“, „Laubwerk“ oder „Blattwerk“ in diesem Zusammenhang fällt. Immer wieder wurde die zuvor stilisierte Pflanze nun als voluminöses Blattgebilde in einer ausladenden Form als Dekorationselement gebraucht. Wobei es sich hierbei nicht um eine reale Verbildlichung der existierenden Pflanze, sondern eine künstlerische Interpretation einer ansonsten sehr klar auseinanderklaffenden Staude handelte. Johanna Honisch greift diese Tradition der freien Interpretation der Pflanze und die mit ihr verbundene Bedeutung als Ornament auf und erarbeitet eine mit Messing überzogene Gipsskulptur, die in einer Wandecke platziert wird. Damit hinterfragt die Künstlerin auch, weshalb eine Staude, die weder aufgrund einer Heilwirkung noch eines anderen generierten Nutzens einen Siegeszug durch die Jahrhunderte der Kunstgeschichte vollzog. Dabei hatte eigentlich kaum jemand diese Staude in seiner realen Umgebung mit eigenen Augen gesehen.

As soon as the name „acanthus“ is mentioned in connection with art, most people think of one of the three classical Greek column orders (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian), because the most recent – the Corinthian – was present in Greece from the end of the 5th century BC and characterised itself as belonging to this order due to the stylised use of the leaves of the spiny acanthus in the capital of a column. However, these Greek architectural forms were handed down traditions and were not recorded in writing. The Roman architectural theorist Vitruvius (1st century B.C.) attempted to explain in an anecdote why this particular plant became generic, but this remains in the realm of legend and can by no means be seen as the actual starting point.

The stylised use of the leaf found its application in murals, statues, book illumination and painting in the following centuries, but with a more or less strong presence. In the Baroque era, the use of the acanthus leaf „experienced“ a climax, with the name „foliage“, „foliage“ or „foliage“ often also being used in this context. Again and again, the previously stylised plant was now used as a voluminous leaf structure in an expansive form as a decorative element. Whereby this was not a real visualisation of the existing plant, but an artistic interpretation of an otherwise very clearly divergent perennial. Johanna Honisch takes up this tradition of free interpretation of the plant and the meaning associated with it as an ornament and creates a plaster sculpture covered with brass, which is placed in the corner of a wall. In doing so, the artist also questions why a perennial plant that has made a triumphant progress through the centuries of art history neither due to a healing effect nor any other generated benefit. Yet hardly anyone had actually seen this perennial in its real environment with their own eyes.

(Text: Gabriele Baumgartner)

Homepage: http://johannahonisch.com/